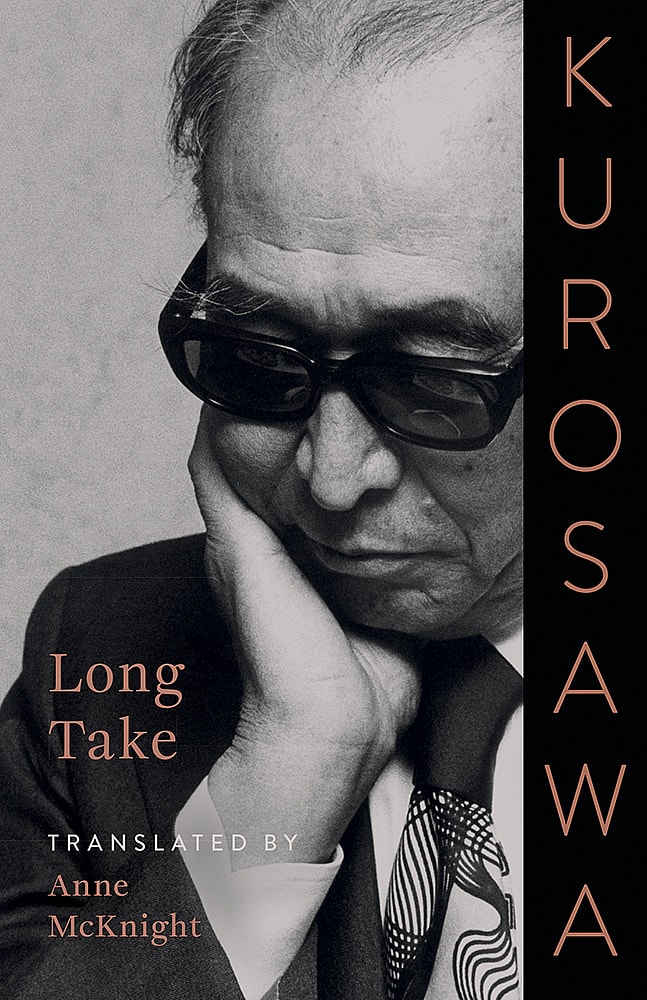

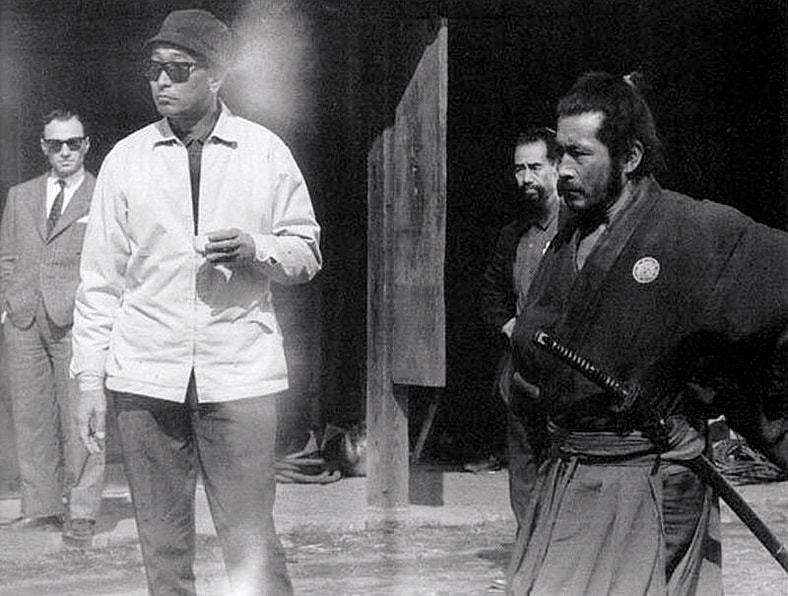

Long Take is a revelatory new portrait of Akira Kurosawa, the masterful Japanese filmmaker whose classic films include Rashoman (1950) Seven Samurai (1954), The Hidden Fortress (1958), High and Low (1963) and Ran (1985). His influence is obvious in movies from Star Wars to The Avengers to A Bug’s Life, and the many overt remakes of his work include The Magnificent Seven (both the 1960 and 2016 versions) and Spike Lee’s recent Highest 2 Lowest.

Compiled one year after Kurosawa’s death in 1998, at the age of 88, Long Take contextualizes Akira Kurosawa through the literature and films that inspired him, from Kabuki to Surrealism to Russian fiction to Hollywood. It will be available to English readers for the first time through a new translation by Anne McKnight, associate professor of Japanese and comparative literature at the University of California, Riverside, being published by the University of Minnesota Press.

One highlight of the book is a section entitled The List, compiled by Akira Kurosawa’s daughter, Kazuko, from conversations with him about 100 of his favorite films. In the following excerpt, we share the first 20 of those films, listed by order of release, not in order of preference, and Kurosawa’s comments about them. It is translated by Anne McKnight—M.M.

The First 20 of Akira Kurosawa’s 100 Favorite Films

1. Broken Blossoms; directed by D. W. Griffith, 1919, USA

Lillian Gish plays a girl who’s very proper—wide-eyed and neatly dressed. Her sister was Dorothy Gish, who was a bit more sensual, while Lillian was a little naive. It was excruciating to watch her character suffering at the hands of her father. I saw her again in The Whales of August, and you can tell she hasn’t changed a bit. She’s now the age of a grandmother, and I was surprised that she’s aged so gracefully.

2. The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, directed by Robert Wiene, 1920, Germany

This is a signature work of German Expressionism, but it still holds up today. You know the look of Expressionist drawings? The whole set is constructed in that aesthetic. There are so many things to learn from those earlier works, you know.

3. Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, directed by Fritz Lang, 1922, Germany

I saw this one as a child, back when Tokugawa Musei was the benshi. My brother dragged me along because he was a benshi too; it was really fun. With that sinister Mabuse as the master of disguises. I saw Abel Gance’s La Roue (The Wheel, 1923) around that time. I remember so vividly the flashback scene with the runaway train; that was really something.

4. The Gold Rush, directed by Charles Chaplin, 1925, USA

Chaplin really had talent as an actor, and comedy is the hardest of all. Making people cry is easy. He also had talent as a director and was really well versed in music; he had so many talents he hardly knew what to do with them all. I think Beat Takeshi is a lot like that.

5. The Fall of the House of Usher, directed by Jean Epstein, 1928, France

Even though it’s a silent and is composed purely of images, you have the illusion of hearing the sound. That use of the image has some amazing expressive powers. Every time I start shooting a film, I make a point of asking myself what it would be like if I shot it as a silent.

6. Un Chien Andalou, directed by Luis Buñuel, 1928, France

It’s shocking — that scene near the beginning where the woman’s eyeball suddenly appears on the screen and the razor slashes across it. Dalí’s scenario is transposed to the screen so vividly, with the shots connected in that random-seeming way you have in a dream. When I was shooting Rashomon it helped me a lot to think back to those techniques of Surrealism.

7. Morocco, directed by Josef Von Sternberg, 1930, USA

Truly a moving picture worth the name. It was made on a very low budget, but it’s really well done—especially the shifts in camera position and the textures of light and shadow that work so atmospherically. I was really impressed by this film.

8. Congress Dances, directed by Erik Charell, 1931, Germany

This is the first movie that used the technique of playback, matching the songs to prerecorded sound. This is a real masterpiece, an operetta. Its songs move in and out of the story, working to develop the characters, and the flow of the camera is just fantastic. I watched it again, and as you’d expect, I thought about the many, many things we should learn from these old films.

9. Threepenny Opera, directed by G. W. Pabst, 1931, Germany

I’ve often thought I’d like to do a remake of Threepenny Opera. Many people have taken a turn at their own versions, but I think Pabst’s is by far the best of the bunch. It’s really a great piece of work.

10. Unfinished Symphony, directed by Willi Forst and Anthony Asquith, 1934, Austria/England

This is such an elegant work; I really like it a lot. It uses Schubert’s music very well and folds it beautifully into the overall drama of how the symphony was left “unfinished,” with only two movements.

11. The Thin Man, directed by W. S. Van Dyke, 1934, USA

Van Dyke was renowned for his action films, so the tempo is really good. It’s based on a Dashiell Hammett novel, and the detective couple and their pet dog were really popular. It turned into a series, but the first one was really the most entertaining.

12. Our Neighbor Miss Yae, directed by Shimazu Yasujiro, 1934, Japan

He was nicknamed Old Man Shimazu, since he had risen through the ranks to make it to director. He paid his dues as an assistant director, and like John Ford or William Wyler, who made their way through the studio system, his works were really in a class by themselves. He was — how can I put it? — a true old-school movie person.

13. The Million Ryo Pot, directed by Yamanaka Sadao, 1935, Japan

Even back when he was an assistant director, Yamanaka was really mild-mannered; he always seemed to be a little in his own world, very subdued. But when he got to be a director, all of a sudden he became quite eloquent; he had a lot of talent. It was such a blow to Japanese cinema when he died much too young. On top of that, the studios haven’t preserved any of his films, which really makes me mad. What the hell are they thinking?

14. Capricious Young Man, directed by Itami Mansaku, 1936, Japan

This work of Itami’s feels especially fresh. He experimented with a lot of different things in this film; it’s a lot of fun to watch. Itami-san always spoke really well of my work, [and] he gave me a lot of good advice; I feel really lucky.

15. The Grand Illusion, directed by Jean Renoir, 1937, France

This film stars Eric von Stroheim, who directed and starred in Foolish Wives; the film overall is amazing, and so is Stroheim. I was lucky enough to meet Renoir when I visited Paris. He’s by far senior to me, so I was surprised when he spoke to me in such honorifics when we met. When we pulled away in the car, I was touched that he watched and waved until we turned the corner.

16. Stella Dallas, directed by King Vidor, 1937, USA

Barbara Stanwyck is famous for this role, which dramatizes that a woman is strong, and a mother will do anything for the sake of her child. I got all choked up at the last scene. The singer Bette Midler played the same role in a remake, and it was also quite a good performance; quite a fine film.

17. The School for Spelling, directed by Yamamoto Kajirō, 1938, Japan

Yamakaji-san was such a good teacher to me. It was really busy on the set, and Yama-san had me doing all kinds of things, and it was work, work, work all the time. Later his wife told me, “He was really happy,” because he said “now Kurosawa is capable of anything.” It’s true, I realized: Yama-san taught me each of these things, from editing to scriptwriting, costumes, and props on up. Now I realize all that running around has paid off, and I’m so grateful.

18. Earth, directed by Uchida Tomu, 1939, Japan

Uchida Tomu had quite an incredible career. I think he was even homeless for a while. He was also an actor, and kind of an eccentric; I think he worked as assistant director for someone who had worked in Hollywood. His big-budget films are good, but I really like his early ones like Unending Advance. Unfortunately, a lot of his films are gone. I really wish they would think of some kind of film preservation law in Japan.

19. Ninotchka, directed by Ernst Lubitsch, 1939, USA

This is quite a sophisticated work. Garbo stars in a part that’s different from her usual role. I was surprised she was so good at comedy. Then again, it was Billy Wilder who did the screenplay, so it’s no wonder the dialogue is so good. Lubitsch has been working since the silent era and made a lot of musicals, cine-operetta films; he is an amazingly talented man.

20. Ivan the Terrible, Parts I and II, directed by Sergei Eisenstein, 1944-46, Soviet Union

Henri Langlois submitted my Rashomon to the Venice Film Festival, so I’m forever in his debt. He told me I better take a look at how Eisenstein used color in the banquet scene of Ivan the Terrible. He also told me I better start working in color, and it’s true, when I saw it, I was bowled over. I started playing with color in Dodes’ka-den, and from Kagemusha on I used it for real. By that time, Langlois had died, and when I said I would have loved to have shown Kagemusha to him, William Wyler’s wife said, “Surely he’s arrived at Cannes (from heaven), and he’s watching alongside us.” Until that moment I’d always hated film festivals, but from then on, I made a habit of going to Cannes.

Long Take will be released February 3rd, from the University of Minnesota Press.

Excerpt reprinted from Long Take by Akira Kurosawa; translated by Anne McKnight. Forthcoming from the University of Minnesota Press. Copyright 2025 by McKnight. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Originally published in Japanese in Akira Kurosawa, Yume wa tensai de aru (Dreams are forms of genius), edited by Bungeishunjū Ltd. Copyright Kurosawa Production, K&K Bros., Bungeishunjū Ltd., 1999. All rights reserved.

Main image: Akira Kurosawa in Kinema Junpo, Special December 1960 issue. Via Wikimedia Commons.

This article first appeared in the fall 2025 issue of MovieMaker.